The late filmmaker George C. Stoney had strong, multifold connections to the Southern Oral History Program’s mission. These connections are place-based and practice-based. Not only did he attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), he wrote and produced films about the South, and advocated for the creation of public access cable television stations which still thrive in cities throughout the southern U.S. And his passion for participatory media-making was not too philosophically dissimilar from that of an oral historian. The oral historian supplies a means–the microphone, a platform–and collaborates with the narrator, or interviewee, who tells his or her story. Stoney worked for years to put the tool in the hands of the narrator: “People should do their own filming, or at least feel they control the content. I’ve spent much of my life making films about teachers or preachers that these people ought to have made themselves.” [1]

Stoney and Place

George Stoney was born and raised in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. There he attended R.J. Reynolds High School; and his father was a pastor for a Church of Christ near the village of Salem where his family also worshipped with the local Moravian congregation (his mother died in 1922). He graduated from the UNC in 1937 having studied English and journalism and lent his skills to writing articles for The Daily Tar Heel, Carolina Magazine, and Greensboro’s Daily News. While at UNC he also performed in minor roles in PlayMakers theater productions, as did his sister Elizabeth a handful of years later. After graduating in 1937, he even talked Raleigh’s News and Observer into publishing stories from the road as he hitchhiked around the state interviewing locals. [2]

From October 25, 1933 The Daily Tar Heel citing Stoney as reporter. Click to enlarge image.

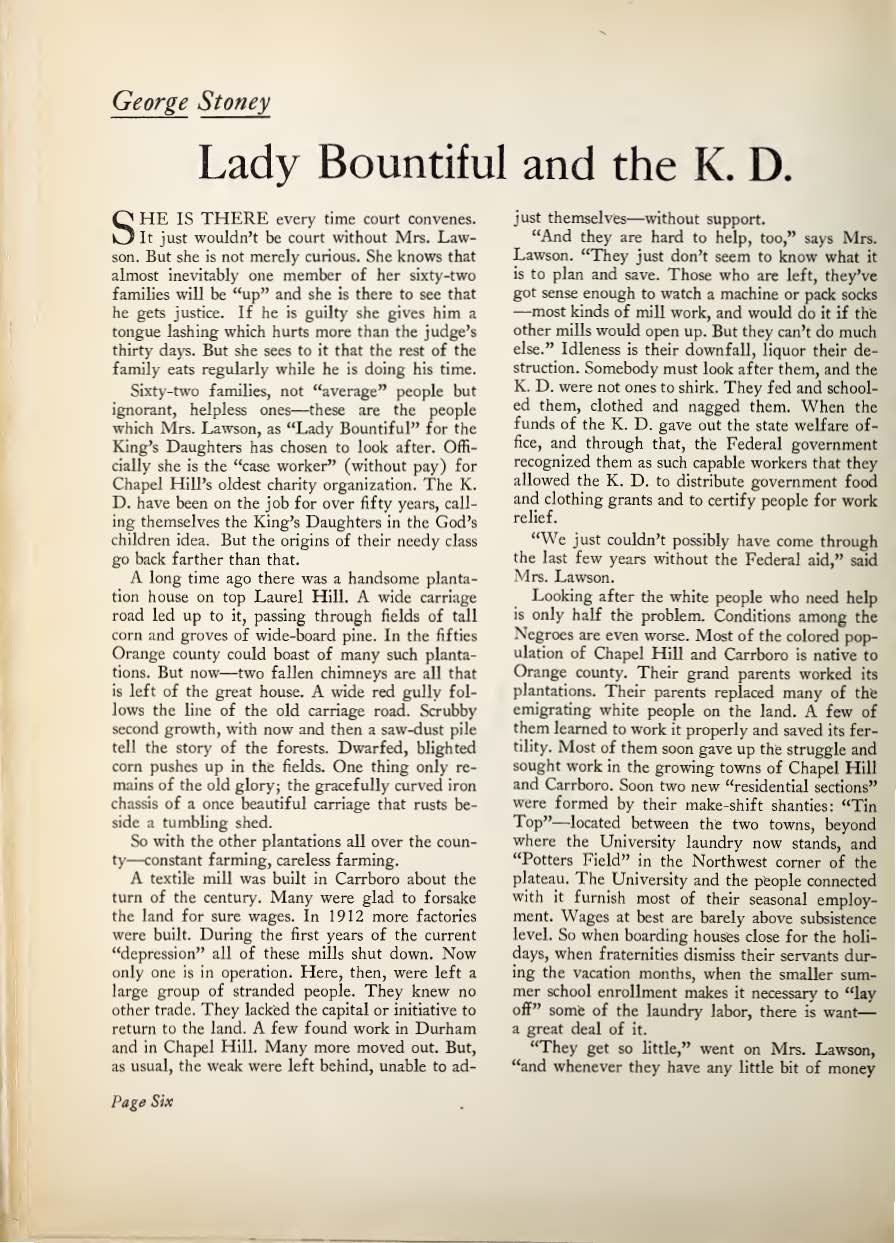

November 1936 issue of Carolina Magazine. Click image to open the entire article.

Stoney’s UNC yearbook picture. Photo credit: Digital NC. Click image to enlarge.

Within a year of graduating, Stoney moved to New York where he wrote for The New York Times and New Republic. He also befriended another UNC alum, author Thomas Wolfe [3]; and often traveled the South with photographer Lewis Hine documenting in stories and images the Tennessee Valley Authority, the poll tax, and other topics which increased “his awareness of race and class divisions.” [4] He soon thereafter conducted social research throughout the South with Gunnar Myrdal and Ralph Bunche on their 1944 publication An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. As publicist for the Farm Security Administration (including writing radio program scripts) he covered the plight of tenant farmers. After World War II, he joined the Southern Education Film Production Service (SEFPS). Located in Georgia, but covering a nine-state area, the SEFPS produced films intended to help government agencies communicate with their constituencies. [5] With them, Stoney scripted a film entitled, Mr. Williams Wakes Up (1944), and directed Tar Heel Family (1951), both shot in North Carolina’s Wayne and Duplin counties. In the following years, while in Washington, DC, he made films for the Association of Medical Colleges, and the during mid-1960s, Stoney was a member of the Advisory Board of the short-lived experiment called North Carolina Film Board, the first state-sponsored documentary film unit. (Among others on the board were documentary filmmaker John Grierson and Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Paul Green. [6]) Late in life, he co-founded the board of directors of Working Films in Wilmington, NC.

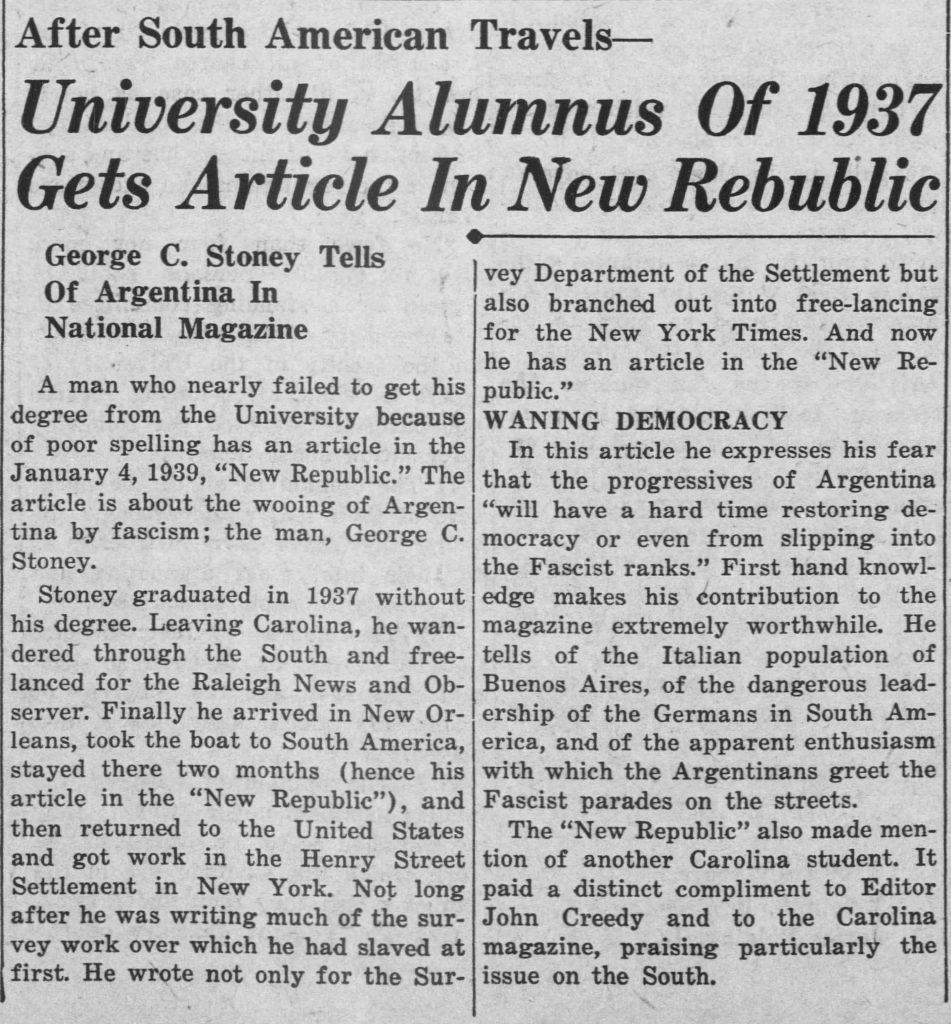

The Daily Tar Heel from January 6, 1939 on Stoney’s article in the New Republic. Click to enlarge image.

All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story (1952). George Stoney’s created the landmark educational film, while working for the Association of Medical Colleges, to educate midwives in Georgia and throughout the South. In Projecting Race: Postwar America, Civil Rights and Documentary Film, Stephen Charbonneau writes about the intent of this film, which was to “set out to promote great coordination between traditional midwifery and the modern healthcare system.” Yet, he continues, “[T]he collaboration at the heart of the film privileges the voice of the midwife, critically thwarting the initial purpose of the project as a whole.”[8] All My Babies was inducted into the National Film Registry in 2002 by the Library of Congress.

From the late 1960s forward, his own production company, George C. Stoney Associates, and various teaching positions led Stoney back to New York (Columbia University), to California (Stanford) [7], and Canada where he ran the National Board of Canada’s Challenge for Change/Société Nouvelle project. Both Challenge for Change and the Alternate Media Center, which he and fellow filmmaker Red Burns founded at New York University (and the new public access television stations they lobbied Congress to support), put film and then video cameras into the hands of community members. Now the interested and engaged citizens could create their content, speak for themselves, and advocate for social change. Over the course of his lifetime he wrote, directed and/or produced over fifty documentaries and television series. Stoney died in 2012.

Stoney’s Practice

Stoney’s advocacy for public access television echoed principles that guide oral historians’ practice: sharing authority, democratization of voices recorded on an audiovisual medium, and community engagement. Regarding notions about sharing authority, Deirdre Boyle, author of Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited, describes Stoney this way: [9]

“Stoney claims he knew almost right from the beginning of his filmmaking career that other people could have made a better film than he except they didn’t have the same ability to listen. He paid attention, and if someone was uncomfortable, he changed things. If a farmer didn’t want to be filmed barefoot, even if his feet were never going to be in the shot, Stoney waited until the man put on his shoes. ‘Being a white, pretentious, middle class man,’ Stoney wryly observes today, ‘I was always a bit shy in the presence of people not of my class. And kind of respectful. I learned to let them set the limits.’”

His methodologies and respect for the interviewee as narrator of his/her own story have been openly praised and acknowledged by oral historians as well as media scholars. The late Clifford M.Kuhn has written about the influence of Stoney’s documentary practice, Doug Boyd about watching his films, and former director and founder of SOHP, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, about his populist spirit. In 1999 she wrote [10]:

“I see George Stoney as the embodiment of the incendiary, leftwing populism that is one of the chief glories of the South’s so often benighted political tradition. I also see him as an exemplary native son, one in a long line of liberals and radicals that have come out of the University of North Carolina.”

Stoney shared with co-director/co-producer Judith Helfand the inaugural 1995 Oral History Association award in the Nonprint Media category for their co-direction and co-production of The Uprising of ’34 (1995, viewable in its entirety with a UNC Onyen, or watch the trailer).

Oral Histories as Primary Sources

Documentary filmmakers often include filmed, videotaped, and audiotaped oral history interviews, although rarely in their entirety, in their films. Moments are selected, clipped, and combined (even with a multitude of other voices) in a way that furthers the maker’s narrative trajectory. Often entire interviews are stored, unseen again, in a personal archive of raw materials and outtakes, on the proverbial cutting room floor. Oral histories are traditionally honored and recorded as primary documents worthy of research in their own right, uncut; and they share this method with historians, filmmakers, dramaturges, and other practitioners. For example, for her 1980 The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter, filmmaker Connie Field and her team of researchers recorded hundreds of interviews with women who, throughout the country during WWII, filled in as welders and riveters while men vacated these factory positions to join the war effort. Hundreds of audiotapes, and some videotapes, are now open for research many years later. [11] Performer, playwright, and educator Anna Deavere Smith has for many of her projects recorded interviews and oral histories with people, and with their permission, embodies them, empathically, on stage.

Recently, Georgia State University Library’s Special Collections and Archives made available digitally for research all of the over 300 hours of interviews conducted for The Uprising of ‘34. For the documentary George Stoney and Judith Helfand, invited their subjects’ participation on camera and incorporated their knowledge and expertise as a driving force behind the narrative. They interspersed interviews with archival footage of 1934 textile mill strikes and related events both to contextualize the narrative for the viewer, but also, as is witnessed in one scene when they show footage to an interviewee, to invoke memories and start conversations. Interestingly, Stoney and Helfand recorded significantly more oral histories than they could possibly use in one film. They were thinking beyond “the movie.” In conversation with this author [12], Helfand shared these and other remembrances about working with Stoney on Uprising. For instance, their intent from the beginning was to document a significant time in southern labor history through the voices of people who were there, and to create an archive of recordings.

Helfand says Stoney was the one who really set the tone for the interviews, and together they were able to help people overcome their reticence and fear of speaking on the topic. In a very real sense these interviews represented perhaps the first or only opportunity to get their stories into the public record. To connect themes in a nonpartisan way and build trust with community members who over the years were hesitant to discuss the strikes (or had heard very little about them), the directors interviewed a chorus of voices who could speak to the events from differing perspectives: mill workers, mill owners, domestic workers who worked in the mill villages, descendants, and others. Black and white interviewees hailed from from Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina, retelling stories about Loray Mills, Parkdale Mill, Cannon Mills, Callaway Mills, Groves Mill, Brown Mill, Modena Cotton Mill, Cherokee Mills, Belmont Mills, and more. Stoney and Helfand wanted to capture a broader, complex and nuanced collective narrative about nontraditional acts of resistance, overlapping concepts of citizenship and community activism, class and race.

George Stoney himself was interviewed in both 1991 and in 2009 here at UNC, and the recordings and transcripts are preserved and made accessible in the Southern Oral History Program Interviews collection. In his 1991 oral history he discusses the trials he faced, and odd jobs he took, trying to pay tuition for undergraduate study at UNC:

The entire 1991 interview:

A-0346

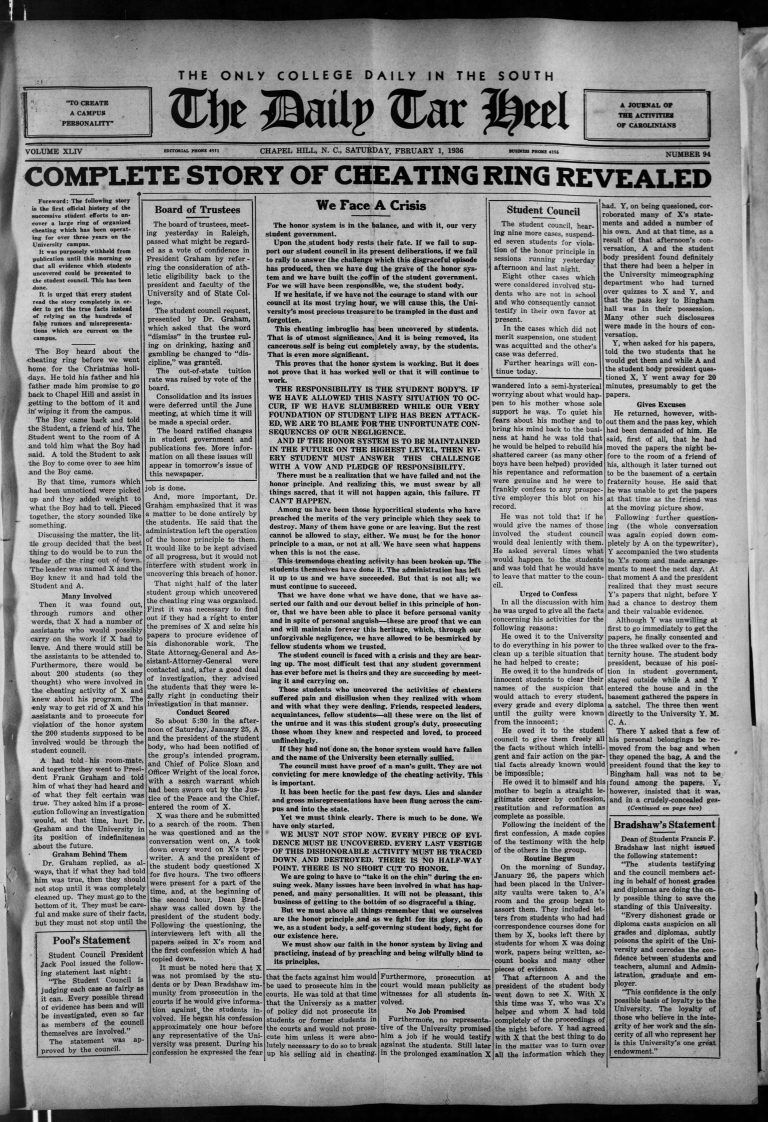

In this 2009 recording he remembers the cramped group housing situation he found himself in the first two years of college, nearly flunking out, social divisions among students, and the cheating ring scandal of 1936:

The entire 2009 interview:

L-0332

The Daily Tar Heel article from February 1, 1936 on the “cheating ring” scandal. Click to enlarge image.

UNC has supported at least two events in Stoney’s honor. In 2009, the Southern Historical Collection in Wilson Library, in collaboration with the Center for Documentary Studies and Full Frame Documentary Film Festival at Duke University, hosted a two-day celebration of his legacy. Back in 1961, the Chapel Hill YM-YMCA hosted a screening of his Booked For Safe Keeping (1960) followed by a panel discussion including a member from the UNC’s Department of Health Affairs.

Click to enlarge image.

George C. Stoney’s papers are deposited and available for research in UNC’s Southern Historical Collection. In the collection, one can find audiovisual materials, production-related documents and correspondences, outtakes and interviews for several films, including All My Babies. Another film in the collection, How the Myth Was Made (1978) is viewable in its entirety with a UNC Onyen, or watch the trailer.

To listen to more interviews with filmmakers in our collection (SOHP’s former director, Malinda Maynor Lowery, is also a documentary filmmaker!), see the SOHP oral history collection filtered by interviewee occupation.

References

Boyle, Deirdre. “O Lucky Man! George Stoney’s Lasting Legacy,” Wide Angle, Volume 21, Number 2, March 1999, pp. 11-18.

Charbonneau, Stephen. Projecting Race : Postwar America, Civil Rights and Documentary Film. New York: Wallflower Press is an imprint of Columbia University Press, 2016.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. “Toasts and Tributes,” Wide Angle, Volume 21, Number 2, March 1999, pp. 137-165.

Jackson, Lynne. “A Commitment to Social Values and Racial Justice,” Wide Angle, Volume 21, Number 2, March 1999, pp. 31-40.

Oettinger, Elmer. “The North Carolina Film Board: A Unique Program in Documentary and Educational FilmMaking,” The Journal of the Society of Cinematologists, Vol. 4/5 (1964/1965), pp. 55-65.

Orgeron, Devin. “Nothing Could Be Finer?: George Stoney’s Tar Heel Family and the Tar Heel State on Film,” The Moving Image 9, no.1 (Spring 2009) pp. 161-182.

Rapport, Leonard. “George Stoney, Writer: The Early Years,” Wide Angle, Volume 21, Number 2, March 1999, pp. 19-25.

Rosenthal, Alan. The Documentary Conscience : A Casebook in Film Making. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

George C. Stoney Papers #4970, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Citations

[1] Stoney in Rosenthal, 346.

[2] Rapport, 20.

[3] Rapport.

[4] Jackson, 31.

[5] Orgeron, 164.

[6] Oettinger, 55.

[7] In later decades he also taught at University of Southern California and City College of New York.

[8] Charbonneau, 61.

[9] Boyle, 15.

[10] Hall, 149.

[11] The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter Project Records, 1974-1980. MC 649 or T-371. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

[12] Phone interview between author and Judith Helfand, November 2, 2017.

by Melissa Dollman