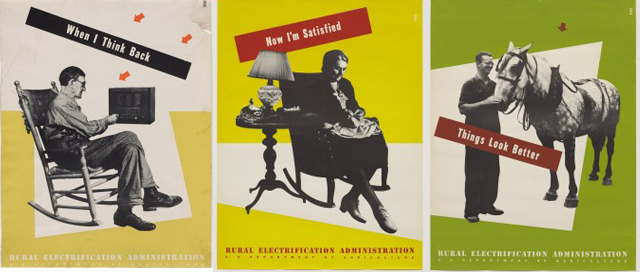

At the beginning of the Great Depression, the vast majority of rural communities across the United States had little or no access to electricity. The cost of connecting to private electric lines was so prohibitive that many rural communities turned to organizing amongst themselves to find creative solutions to electrification. In 1935, the federal government established the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to support the formation of rural electric cooperatives. Over the following decades, this initiative thoroughly transformed rural life, extending electricity to rural businesses, farms, schools, and households and establishing a large network of utilities cooperatives that continue to provide services to rural areas today.

At the beginning of the Great Depression, the vast majority of rural communities across the United States had little or no access to electricity. The cost of connecting to private electric lines was so prohibitive that many rural communities turned to organizing amongst themselves to find creative solutions to electrification. In 1935, the federal government established the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to support the formation of rural electric cooperatives. Over the following decades, this initiative thoroughly transformed rural life, extending electricity to rural businesses, farms, schools, and households and establishing a large network of utilities cooperatives that continue to provide services to rural areas today.

This collection includes 44 interviews gathered by the North Carolina Association of Electric Cooperatives in honor of the 50th anniversary of the REA in the 1980s. In these interviews, electric co-operative leaders, members, and other rural residents from across North Carolina reflect on the role of co-ops in rural electrification and the impact of electricity on their daily routines and community life.

While many rural residents initially viewed electricity as a luxury, they quickly discovered that it brought much more than creature comforts and conveniences. Electric power profoundly transformed agriculture, as milking machines, electric fences, and water pumps changed the lives of people, animals, and agricultural crops alike. Many oral histories in this collection attest that electrification brought a notable increase in leisure time, particularly for women, as innovations as wide-ranging as electric irons, washing machines, and cold-cut lunch meats dramatically decreased the labor of housework. In this newfound leisure time, rural residents enjoyed radio and television programs that provided increased exposure to wider horizons of information, music, and other cultural forms that were once exclusive to urban elites.

While many rural residents initially viewed electricity as a luxury, they quickly discovered that it brought much more than creature comforts and conveniences. Electric power profoundly transformed agriculture, as milking machines, electric fences, and water pumps changed the lives of people, animals, and agricultural crops alike. Many oral histories in this collection attest that electrification brought a notable increase in leisure time, particularly for women, as innovations as wide-ranging as electric irons, washing machines, and cold-cut lunch meats dramatically decreased the labor of housework. In this newfound leisure time, rural residents enjoyed radio and television programs that provided increased exposure to wider horizons of information, music, and other cultural forms that were once exclusive to urban elites.

Electricity also brought lunchrooms to many rural schools, which former classroom teacher H.E. Daughtry describes as an important step foward for child nutrition and educational performance:

Most of the oral histories in this collection emphatically affirm that rural life improved with the advent of electric power, but some also articulate a sense of loss for former ways of life. Many participants say that rural communities were more interdependent before electrification, neighbors intimately connected across families and reliant on each other for help on the farm.

The introduction of radio and television meant fewer evenings dedicated to reading, visiting neighbors, and conversation. Mrs. W.D. Eliot describes generational shifts after electrification:

Some interviewees identify electrification as a significant move towards urbanization, as rural communities grew in size and lost their sense of closeness and traditional character. Additionally, the turn towards agricultural mechanization made farming an increasingly capital-intensive endeavor, requiring initial investments in equipment and annual budgets for the chemical fertilizers and herbicides that accompanied industrial farming practices.

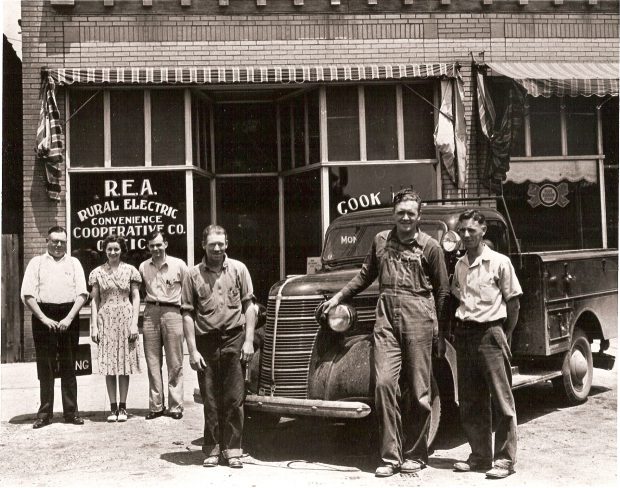

Because private power companies had very little economic incentive to extend service to rural areas, the non-profit co-operative model proved vital for ensuring the expansion of service territories into rural areas.

The rural projects that private power companies undertook during this era often served far-off communities rather than the rural areas where they were located, as Fredda Davis describes in the case of a proposed New River dam:

The co-operative model not only allowed many rural areas to access electricity for the first time, but also to keep costs low, retain local control over their electric networks, and return surplus to their communities. While they were encouraged and funded through federal programs during the New Deal era, co-ops built on long-standing networks of mutual aid and collective infrastructural improvement in rural Southern communities.

Dema Lyall discusses a stereotype-defying early telephone system in her Appalachian community:

Early electric co-operatives confronted numerous obstacles. Farmer and electric co-op member Sam Oswalt says that private power companies obstructed their progress by securing right-of-ways from landowners even when they had no intention of laying power lines in a timely way. While structurally democratic, co-operative boards rarely represented all local constituencies, often excluding African-American farmers and white residents from more remote areas, and service provision remained uneven by both race and class. Former co-op lineman John Costan and several other participants also argue that as co-operatives expanded, many began to function more like corporations, reducing the direct participation of members and emphasizing economic competitiveness. And Costan remembers the dangers of early electrification, as rural residents attempted to help linemen repair damaged lines and were sometimes electrocuted. Last but not least, the specter of socialism often plagued co-operatives’ public outreach attempts, as private companies attempted to avert competition by taking advantage of the “red scare” and accusing co-operatives of "un-American" activities.