Durham’s Anti-Expressway Organizing

In 1959, a four-lane expressway was making its way through the heart of Durham, North Carolina. Riding on the coattails of the 1956 Interstate Highway Act and adopting city revitalization techniques pioneered by urban renewal leaders a decade earlier, the East-West Expressway, now known as Highway 147, triggered 30 years of business-and automobile-oriented redevelopment throughout Durham, fragmenting the city and leaving a path of destruction in its wake. Set directly in the expressway’s path were several working-class black communities; communities that would pay the ultimate price in the name of economic growth and prosperity. Some communities, however, took note of the relocation and displacement occurring in neighborhoods impacted by the highway and mobilized against the expressway in an effort to keep their communities intact. Crest Street was such a community.

This collection includes six oral histories gathered by UNC-Chapel Hill graduate Emily Goldstein in support of an honors thesis in Geography titled “We Shall Not Be Moved: A History of Anti-Expressway Organizing by the Crest Street Community in Durham, North Carolina,” and the creation of a community archive titled the Crest Street Community History Project. In these interviews, Crest Street leaders, advocates, and attorneys reflect on the movement to save Crest Street from the expansion of the East-West Expressway, a movement that maintained Crest Street as a unified community and a thriving example of residential empowerment in the face of seemingly unstoppable urban forces.

Complete interviews and transcripts are available here in the Southern Oral History Program database. To listen to the entire SoundCloud playlist, you can find it here.

The Fight for Crest Street

Map of Crest Street Community showing affected areas of the community and the path of the Expressway. Photo Credit: The East-West Expressway Expansion Controversy, Duke University Sites.

The Crest Street community began their battle against the East-West Expressway in 1973 when the highway was slated for further expansion. Its new path was to cut directly through the center of the community, as well as the historic New Bethel Baptist Church. After witnessing the destruction of other black communities in the area, specifically the Hayti community, Crest Street residents swore that they were not going down without a fight. Over the course of a decade, Crest Street leaders attempted to find a way to keep their community unified. Residents met with the City Council of Durham, the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT), and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to explain the importance of the community and the family-like bonds that they shared. One of the most important factors in the community’s battle was the presentation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), required by the National Environmental Policy Act (1970) for any project that is determined to “significantly affect the quality of the human environment.” A local activist group, ECOS (Environmentally Conscious Organization of Students) filed a lawsuit in the Durham district court to stop the construction of the highway while the Environmental Impact Statement was drafted.

“Stop the Expressway” shirts were sold to fund the opposition to the Expressway. Photo Credits: Open Durham, John Schelp.

In 1978, while the EIS was being prepared, the city of Durham released their plan for the Crest Street Community, which involved dispersing the residents to various locations throughout the city. Community members banded together and hired attorneys Mike Calhoun and Alice Ratliff through the North Central Legal Assistance Program, as well as traffic engineering consultant Robert Morris to counter the NCDOT’s plans. In addition to the attorneys, another key player in the fight against the expressway was Duke University sociologist Elizabeth Friedman, who authored a family/community impact survey documenting the cohesiveness and tight-knit familial network of Crest Street.

With the help of attorneys Mike Calhoun and Alice Ratliff, the community filed an administrative complaint using Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act with the U.S. Department of Transportation. The complaint alleged that the planning of the East-West Expressway was racially motivated having both a prejudiced intent and impact. In 1980, the community received a response from the U.S. Department of Transportation Director of Civil Rights Ellen Feingold, written to NC Secretary of Transportation Tom Bradshaw:

“The proposed alignment which shows an interchange displacing virtually the entire black community along Crest Street would entail extremely adverse and disproportionate impacts on blacks as compared with Whites in the surrounding area in terms of displacement, relocation, and general community disruption.”

The NCDOT was forced to come up with a different plan. The NCDOT then formed the East-West Expressway steering committee, which was comprised of members from the NCDOT, FHWA, the City of Durham, Durham County, the Crest Street Community Council, Duke University, Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, and the People’s Alliance. After delays and restructuring due to a rezoning conflict between Crest Street and the City of Durham, the steering committee was reformed with fewer parties involved: only the NCDOT, FHWA, the City of Durham, Duke University, and the Crest Street Community Council.

This smaller council helped streamline conversations between the Crest Street Community Council and the other stakeholders. Meetings were now held at New Bethel Baptist Church, a key bargaining point by the Crest Street Community Council. Residents of Crest Street wanted to bring representatives from the NCDOT and the FHWA to their homes in order to highlight the community the Expressway was set to destroy. After many more months of negotiations, the NCDOT determined that there was a sufficient amount of land within the Crest Street community to build both the Expressway and maintain the neighborhood. While the Crest Street community was unable to stop the Expressway in its entirety, it was able to maintain community cohesiveness and stay intact as a unit, moving to an undeveloped area of land adjacent to the original community. This was a major victory for the Crest Street community, establishing a model for other black communities of organization and perseverance.

To learn more about the origins of the fight for the Crest Street community, listen to this clip by Mike Calhoun, one of the lawyers employed by the Crest Street Community Council:

The Voices of Crest Street

Willie Patterson, the former president of the Crest Street Community Council. Photo credits: Nina Tan.

Six of the leaders in the fight for the Crest Street Community shared their story through oral histories conducted by UNC student Emily Goldstein. These interviews focused on the lives of Crest Street residents and activists, such as Willie Patterson, Maedell Gattis, and Betty Johnson as well as allies to the Crest Street cause like attorneys Mike Calhoun and Alice Ratliff.

Seeking to expand upon the limited existing literature on Crest Street, Goldstein focused on documenting the history of the Crest Street community through the lens of community history and resident experiences. Goldstein centered her questions on the residents' childhoods, what the community was like before the Expressway and the ways that the community has persevered since the redevelopment. Community members also discussed the specific tactics they used for mobilization and the critical role community organizing played in saving Crest Street. One community leader, Betty Johnson, discusses the ways that the Crest Street Community Council educated and mobilized Crest Street residents:

In addition to traditional organizing tactics, members of the Crest Street Community showed their humanity through non-traditional methods, such as sharing meals with members of the Department of Transportation:

Community leader Betty Johnson also cites religion as one of the most important factors in keeping morale high during trying times, even calling prayer “the glue that kept us all together”:

For community leader Maedell Gattis, Crest Street’s greatest legacy is that the community "stuck together, fought for their rights and won.”

History of Crest Street

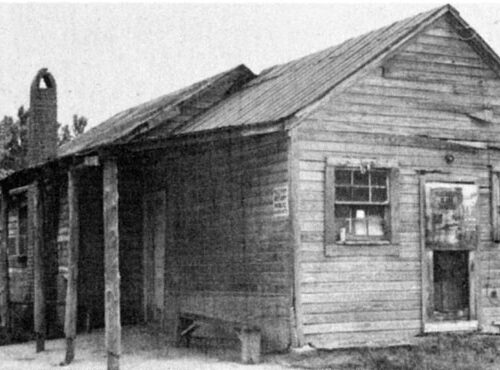

Settled during the 1860s on the outskirts of Durham as an agricultural community for former slaves, Crest Street was once known as Hickstown after its white landowner Hawkins Hicks. Located in the western part of Durham, the small community is bound on the north by Crest Street and on the west by Bass Street. Despite the racism and systemic oppression rooted in Crest Street’s origins, Crest Street managed to thrive, growing and becoming a self-reliant community. In the early 20th century, the community mirrored the growth in Durham. Duke University and its surrounding medical campus during the 1920s and 1930s generated many jobs and nearby residents were able to gain steady and secure employment, albeit within the strictures of Jim Crow. Crest Street residents were able to achieve “a modest but stable standard of living over a long period of time, filling a need for laborers, food service workers, housekeepers, and grounds maintenance workers, and farming part-time on open parcels of land in the vicinity” of the neighborhood. By the 1970s, the community had more than 200 households with over sixty percent of those residents employed by Duke University.

Unseen by much of the surrounding Durham community, Crest Street was home to many community-based, independently-owned businesses. A nursery school, a rest home, grocery stores, barbershops, and more were all located within the community, providing both convenience and livelihood for residents. The high degree of self-reliance and steady employment translated into a community with longevity—the average length of residence was 36.5 years and 44.5% of the community worked within a mile of Crest Street. Built within this stability was a tight neighborhood network of extended family members. Many residents call Crest Street a “family community,” as over 65% of residents reported in 1978 having relatives living in other households in the community. Beyond the emotional and familial connections, “the kinship network” was critical for the economic survival of many households where the children of working parents, as well as the disabled or elderly, were often cared for by retired relatives living nearby. All of these characteristics allowed Crest Street to be a highly autonomous and self-sustaining community despite a low average household income. In 1978, 66% of households reported a monthly income of under $400.

Community leader Maedell Gattis describes the kinship network and the sense of community cohesiveness within Crest Street:

To learn more about the beginnings of the Crest Street community and New Bethel Baptist Church, listen to these clips from Crest Street Community Council founder, Willie Patterson:

References

Emily Goldstein’s thesis, “We Shall Not Be Moved: A History of Anti-Expressway Organizing by the Crest Street Community in Durham, North Carolina”

“The East-West Expressway Controversy," Duke University publication

Digital exhibit created by Emma Miller