In 2012 and 2013, the SOHP conducted a project on early African American credit unions in North Carolina. Community leaders established their own credit unions as an alternative means of saving and borrowing money during the Jim Crow era. The Self-Help Credit Union in Durham raised this idea with SOHP, pointing out the value of these early credit unions in their communities. The interviewees reveal how they and their communities adapted to segregated banking by creating and growing their own credit unions. Even after many of these racial barriers fell, Black credit unions continued to grow and merge with others into the 21st century.

In 2012 and 2013, the SOHP conducted a project on early African American credit unions in North Carolina. Community leaders established their own credit unions as an alternative means of saving and borrowing money during the Jim Crow era. The Self-Help Credit Union in Durham raised this idea with SOHP, pointing out the value of these early credit unions in their communities. The interviewees reveal how they and their communities adapted to segregated banking by creating and growing their own credit unions. Even after many of these racial barriers fell, Black credit unions continued to grow and merge with others into the 21st century.

Browse and listen to the full interviews here.

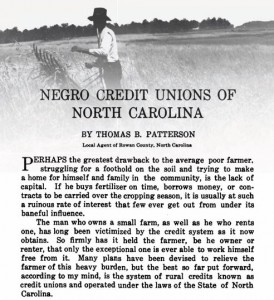

The Southern Workman, a journal published by the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, was one of the first to report on Black credit unions in North Carolina.

The first credit union in North Carolina was founded in 1916 in a rural community in Durham County, most likely for white farmers, while the first credit union established by Black North Carolinians was founded two years later in Rowan County. Black citizens had set up another eight credit unions by 1920. During the 1940s, the number of Black credit unions rose to 55, giving North Carolina nearly as many as all other states combined.

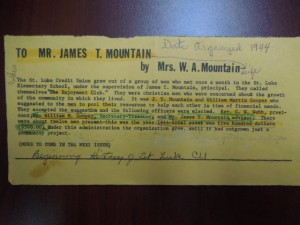

St. Luke newsletter

St. Luke Credit Union in Bertie County was established in 1944 by a group of about 12 African American men with $500.

James T. Mountain remembers his father, James T. Mountain Sr., as part of that founding group, explaining why they felt it was necessary because the white-owned local bank would not deal with African Americans.

African American teachers were drawn to credit unions, as William Kennedy explains in the following clip. From Salisbury, Kennedy joined the Rowan County Teacher’s Credit Union, later becoming manager and helping with its merger into the First Legacy Community Credit Union.

At one point during the 1970s, Reverend Joseph L. Battle applied for a loan at a bank in Halifax County, but was denied. With a friend’s help, he went back to the bank and talked to someone else, who approved the loan. Since he was Black, Battle needed someone with standing to vouch for him at the white-controlled bank. This experience motivated Battle to join a new credit union at J.P. Stevens in 1984, and he later served as chairman once it separated from the company and became the Industrial Credit Union before later merging with the Generations Community Credit Union.

Timothy Bazemore is a Bertie County native and early leader within the St. Luke Credit Union. As he helped establish St. Luke, he took on much of the collateral, motivating him to see it succeed.

Originally from Kannapolis, Mason McCullough later moved to Statesville and joined the Statesville Credit Union. He later became its manager, but as a small credit union with mostly African American members, it was never financially secure, as he describes in this clip. The Statesville Credit Union later merged with the Rowan Teacher’s Credit Union.

In 1952, Charles Sanders helped found the Greater Kinston Credit Union in Lenoir County. Among its clients were black sharecroppers and tobacco and textile factory workers. Looking back on his life, he remembers his neighbors, a poor white family, and the kindness his mother and father showed them as the inspiration for later wanting to help people through a credit union.

Saundra Scales’s first job was at the Mechanics and Farmers Bank in Durham, but she climbed the corporate ladder and worked with a number of credit unions. During her time with the School Workers Federal Credit Union, she remembers the sexism she faced at the workplace, but also how her ideas brought innovation and growth to the company.

St. Luke merged with Generations Community Credit Union in 2002.

Amaza Byrd worked for the St. Luke Credit Union in Bertie County for 22 years, eventually becoming a manager. When asked if St. Luke made a difference in people’s lives, her answer was precise and emphatic.